|

|

|

|

Why salmon are going extinct

Cumulative impacts devastating December 2009 by Kevin Collins It can be confusing to hear that expensive projects are being conducted to benefit an endangered species, but at the same time be told that the animals are continuing to die out. The reasons are both simple and complex. Depending on where you look in California, the problems for salmon may be an issue of a dam built in 1955 or a stream pumped dry in the summer of 2009. All these impacts combine to harm these animals.  This large male coho is in spawning condition. California Department of Fish and Game. First it is necessary to understand that vast regions of the state were forever eliminated as salmon habitat during the dam building frenzy of the first 70 years of the 20th century. The Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountains once provided thousands of streams where salmon could reproduce. Salmon are now blocked from huge parts of their former range. It was assumed that fish hatcheries could replace streams for the spawning and rearing of young fish. In the long run this strategy has not worked, but it has taken decades for people to learn this. The salmon that remain in the Sacramento, the Feather, and other interior rivers where dams were built, are nearly all hatchery origin fish. Their genetic diversity has been severely reduced. These artificial fish populations do not have the strength and adaptability to replace wild fish because natural selection was not at work in the hatchery to allow only the fittest offspring to survive. Heavy fishing pressure has also affected the life cycle of Chinook (king) salmon. Some of these big salmon once spent up to five years in the ocean, but few Chinook live past three years before being caught prior to reproducing. The Chinook life cycle is now less diverse making these fish more vulnerable to droughts and poor ocean condition. Hatchery fish may go out to sea but fewer and fewer return to spawn. Many people tend to think of fish as automatons. They are actually complex wild animals. Salmon must possess the ability to navigate, to evade predators, to find food, and reproduce in constantly changing environments. Life in a hatchery concrete trough being fed food pellets does not select for survival traits. In only a few generations, many fish from a hatchery have reduced ability to survive in the wild. As major rivers and their tributaries are dammed and diverted, fish disappear. The tiny number of tributaries still accessible to wild fish on the Sacramento River may not be enough to sustain these animals. The San Joaquin River was turned into a dry riverbed decades ago. It is now supposed to be restored, but this is an experiment, and the headwaters will remain inaccessible to salmon. Diversion projects, such as the pumps in the Delta that send water south, cause considerable juvenile salmon mortality. The many coastal rivers that are still open to the ocean are often severely damaged by both current human actions and destruction that occurred long ago. Large rivers in parts of Northern California that appear wild and remote from human disturbance are not healthy for salmon either. Most have been dramatically impacted by humanity. We have few true refuges for salmon left. Every creek remaining that supports salmon is important. The Salmon River in Northern California is a major Klamath tributary. It was damaged by dynamite and placer mining long ago. Huge amounts of rock were dumped into its channels. Now this excess rock in the river captures too much heat from the sun. This heat is transmitted into the water during the low stream flows in the summer. Salmon die in warm water. The river still looks beautiful. The water is clear blue, but the river channel is severely damaged in complex ways that took scientists a long time to understand. It takes a long time for the river to move out this excess rock and sediment. This river may not recover during the lifespan of anyone alive today, and salmon do not have much more time left. Logging and other impacts continue to cause additional long-lasting damage. The Mattole River drains California’s Lost Coast. People have spent decades trying to restore salmon in this river. Salmon restoration itself began with people who live in the Mattole watershed. This watershed was very heavily logged through the 1960s, and clear-cut logging continues today. The giant, old-growth trees that narrowed and shaded the river were all cut down. The river channel structure was held together by the forest. When the forest was destroyed, massive soil erosion and floodwaters ripped out the steam banks. Both the upper tributaries and the main stem were filled with sediment. The river is now too wide, shallow and warm to be good for salmon, though small populations of several species continue to hang on. It could take hundreds of years for the Mattole River to return to its original productive condition. A lot of work has been done in the Mattole by people who love wildlife, but they cannot undo the massive damage. A giant forest must grow back, recolonizing river banks and narrowing the channel. People can only hope to reduce current impacts such as eroding road systems and logging near the stream. One organization is helping homeowners purchase big water tanks so they can stop pumping the headwaters during the summer. This work is very creative and necessary, but it will not stop all summer water diversion nor end droughts. These accounts of habitat loss on the Salmon and the Mattole are just two examples of how our river systems were severely degraded in fundamental ways. Similar events occurred all across California. Today, few rivers and creeks have conditions that support salmon as they once did before Europeans. The habitat restoration work that would address these basic problems has hardly begun. What about the regulatory agencies? This July DFG recommended that the forestry regulations for salmon streams on the Central Coast actually be weakened! On January 1, 2010 the stream protection rules for logging in the Santa Cruz Mountains will be weaker than anywhere else on the California Coast. Instead of habitat stewardship, we get politics.

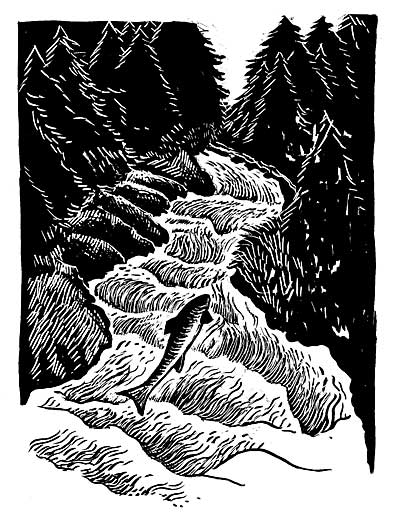

The governor appoints the Director of Fish and Game and the Water Boards. It matters little whether the governor is a Republican or a Democrat. Salmon have never received the protection they need from DFG or any other state agency. Many dedicated and conservation-minded people have joined the Department of Fish and Game only to discover that their superiors will not allow them to protect California’s wildlife. The federal agency charged with protecting salmon is the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) which is part of NOAA. This agency is actually very small, and its people are spread thin. It is subject to political constraints similar to those that affect DFG. NMFS has regularly taken much stronger positions in defense of salmon than has DFG. If the recommendations issued by NMFS were followed, salmon might have a chance. Much more political support will have to be given to NMFS before this will happen. These few examples will hopefully give you a window into the huge, long-term, problems that salmon face. As California’s human population expands, the impacts upon these fish only become greater. Local situation Decades of intensive stream-side development, road building, logging, sand mining, agriculture, and water extraction have added and intensified impacts upon fish. In Santa Cruz County salmon are subject to every impact, even dams. The headwaters of Newell Creek was once salmon habitat. This site is now Loch Lomond Reservoir. Several North Coast streams in Santa Cruz County have diversion dams that supply water to the City of Santa Cruz. These dams reduce streamflow and block fish access. Water pollution is a problem almost everywhere. Polluted runoff roars off streets and into our creeks. The lower San Lorenzo River is a disaster area for fish. It is hot and polluted with very little fresh water in the summer. Much of the water is taken by the City of Santa Cruz. River-mouth lagoons are very important nursery habitat for steelhead but this need has been virtually ignored in the way our rivers are “managed” for flood-control. The Soquel lagoon still works for steelhead due to good management by the City of Capitola, but it is hardly pristine. The soil erosion rates in the Santa Cruz Mountains are truly intense. The San Lorenzo River alone transports massive volumes of sand and silt every year. Every time anyone carves up the landscape, this erosion rate increases. Every driveway, logging skid trail, and bare spot adds to the flood of sediment entering local streams. Salmon egg mortality is high when gravel is laden with sand and silt. It is amazing that they manage to spawn at all. We have many good land use codes and environmental regulations on the books in Santa Cruz County. They are not enforced. If County Code were actually enforced, salmon would have a chance. Good intentions are not enough; good enforcement is also needed. The salmon restoration efforts help but are often tiny in comparison with the scale of the problems. Often restoration money is allocated based on human needs and not upon what is actually best for the salmon. The Santa Cruz County Resource Conservation District recently spent $800,000 to replace a culvert with a bridge over a small waterway. This project might help, but $800,000 is a lot of money to improve fish passage into one tiny creek. The big projects that would actually restore stream habitat are very hard to tackle. Many landowners, water districts, and municipalities may be involved, and some will never cooperate. The permits can be duplicative and cause long delays. These types of problems hinder our ability to select projects that would be best for the wildlife.  Sharon Williams It is time to be honest with ourselves. Salmon are disappearing and the steps we have taken so far are clearly not enough. We could help these splendid animals thrive once again. Salmon are remarkably resilient, but they do not have much time left. Relatively small changes in our behavior are necessary to begin to save salmon populations. However some people will have to give up privileges that they currently enjoy. This cannot be avoided. So far our society has decided to allow habitat destruction to continue rather than to confront the social and political problems. Regulations are politically unpopular, and politicians are reluctant to enforce them. The public will have to demand effective rule enforcement or salmon will not survive. We cannot just pick out a few creeks and decide to protect them alone. We need to protect all the remaining salmon habitats and begin to restore areas that were lost. Salmon once supported fishing ports from Alaska to Monterey. Many Native American cultures founded their economies on salmon. Salmon join the mountains to the oceans and tie together a web of life that connects grizzly bears to mayflies. Native Americans did not take all the fish nor did they destroy their rivers. We know what is necessary to save salmon, and it is physically possible to do it. It will take a long-term commitment and the willingness to enforce laws that have long been ignored. We cannot continue to destroy the biological productivity of the earth. If you have ever been lucky enough to watch salmon jumping a waterfall and spawning in a tree-shadowed creek, you understand why these animals inspired reverence from every native culture.

|

|